Earlier this week, a remarkable photograph changed the nature of the Canadian election campaign. The death of a two year old boy, Alan Kurdi, whose body was washed up on a beach became a symbol of Canada’s inability or reluctance to deal with the Syrian refugee problem.

Up to this point in the election, the economy was seen as the ballot question. Each party was trying to persuade voters that it would be the best manager of the economy. The recent GDP data were the subject of much hand wringing and debate. Were we in a technical recession or not? If so, what does that mean for which party should be entrusted to manage it?

All this changed on September 3 when newspapers around the world (like the Times of London, Washington Post) led with the same story of a family whose attempt to leave Syria resulted in the death of two children and their mother. The largest circulation paper in Canada, The cover of the Toronto Star, on the left, led with a variant of the Globe’s picture, on the right.

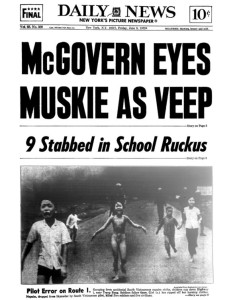

These images are great examples of how quickly a photograph can set the policy agenda both for the media, who saw the importance of the issue as reflected in their front pages, as well as the public for whom the issue may become a ballot box question. There are other notable examples of a photo changing the course of a policy. In 1993, at the height of yet another famine in Sudan, Kevin Carter took a photo that would change the course of famine as an important humanitarian issue as well as his lif e. (Carter committed suicide months after he won the Pulitizer price for the photo). The famous photo of Phan Thi Kim Phuc running from a U.S. napalm bombing in Viet Nam also served to change the course of the Viet Nam war. Interestingly, as the photo from the New York Daily News on the right shows, while it was newsworthy, the photo still was secondary to domestic politics.

e. (Carter committed suicide months after he won the Pulitizer price for the photo). The famous photo of Phan Thi Kim Phuc running from a U.S. napalm bombing in Viet Nam also served to change the course of the Viet Nam war. Interestingly, as the photo from the New York Daily News on the right shows, while it was newsworthy, the photo still was secondary to domestic politics.

In 1989, during the Tiananmen Square uprising in Beijing, a lone solitary figure stood for both individual rights and freedom. So called ‘tank man‘, the anonymous young man who defied the government by standing in front of tanks became emblematic of that conflict: the lone, unarmed solitary figure standing up to an oppressive state.

What all these have in common is that one photo stands for the complexity of a policy issue that until the time the time of publication did not have traction in the public imagination. These images in the words of Susan Sontag are “inexhaustible invitations to deduction, speculation and fantasy”. The invite us to wonder what is at work and how we got to this place. As such, they are snapshots frozen in time but also invite us to speculate on the history that led to that instant. Why is a girl running naked? What would motivate a man to stand in front of a tank? All are notable because they ring of authenticity and appear not staged. They seem to capture a moment in time with the photographer merely a solitary witness to an event. But of course, they are successful because of the photo’s composition and construction.

Great photos like these are about selection and reduction. The choice of image and the elements within are integral to their meaning. I would argue that the Globe and Mail’s photo is more effective than the one used in the Toronto Star, UK Times or Washington Post because of the selection of the stark image of young Alan Kurdi on the beach instead of in a police officer’s arms. In the latter, we can imagine Alan is being saved or is being protected. In the Globe‘s picture, no such inference can be imagined. Death is obvious and the innocence of that death is magnified by the elements of the photo such as the velcro shoes and the hint of a cartoon (or is is picture of a superhero?) on his shorts. The discussion by the Conservatives is that the complexity of the Syrian refugees cannot be reduced to one single picture. And they may be right. But these photographs, through an emotive and compelling visual that sears in our brain, are far more persuasive than any logical argument. This effect is what Roland Barthes called punctum which according to Kasia Houlian is “an intensely private meaning that is suddenly recognized and consequently remembered.” It’s not about the image; it’s about what image does to you.

The photo of young Alan has an agenda setting function by putting the plight of Syrian refugees on the public agenda. And because of that, the public will now judge leaders on their capacity to respond to those issues they deem important which now includes our refugee policy. Such a powerful image will not be mitigated by logical appeals or statistics. The best that the government can can hope for is that come voting day, the policy agenda has moved on.